Recognising and Supporting Indigenous Leadership in Conservation

This article is published as part of the 30th edition of ‘A Call from the Wild’, IUCN’s quarterly Species Conservation Action newsletter. This edition focuses on indigenous communities and their importance to conservation.

Dr Nathan Bennett, Chair of the IUCN People and the Oceans Specialist Group, and Dr Ameyali Ramos Castillo, Deputy Chair of the IUCN Commission on Environment, Economic and Social Policy, explore the importance of working with Indigenous communities in conservation.

Research shows that the rate of tree cover loss is less than half in community and indigenous lands compared to elsewhere and that Indigenous peoples and local communities are investing substantially in conserving their territories – up to $US1.71 billion. Furthermore, Indigenous land management practices have been shown to be as effective as protected areas for biodiversity and species conservation. Therefore, working with Indigenous communities and drawing on their experience in land management practices is critical to protecting large areas of habitat where people have lived in harmony with the landscape and wildlife for generations.

There are numerous examples from around the world that demonstrate how cultural norms, traditional knowledge and management practices of Indigenous peoples have maintained and safeguarded local species. In Australia, Aboriginal peoples avoid killing female game animals and they have norms regulating when and where they are able to hunt for wild game. In Guatemala, indigenous governance systems have specific wildlife protection norms around the Quetzal because of its spiritual value, which research suggests are directly responsible for the survival of the bird species today. In Ethiopia, traditional healers manage and care for forests that house important medicinal plant species.

An active presence on the land and continuity of subsistence practices enables these indigenous stewardship efforts and biodiversity to persist. Yet historically, Indigenous peoples were, and in some cases are still being, removed from their lands and territories in the name of conservation. However, more and more evidence is reaffirming the need to recognise and support Indigenous leadership in the conservation of species and habitats. Globally, there is an increased awareness of the need to collaborate with Indigenous groups who often see themselves as custodians of nature.

So what is being done in the conservation community to more effectively support the role of Indigenous peoples in conservation? Many in the conservation community have been and are taking proactive steps to collaborate with Indigenous peoples on conservation projects. Below we highlight a few important lessons.

Respecting Indigenous lands and tenure.

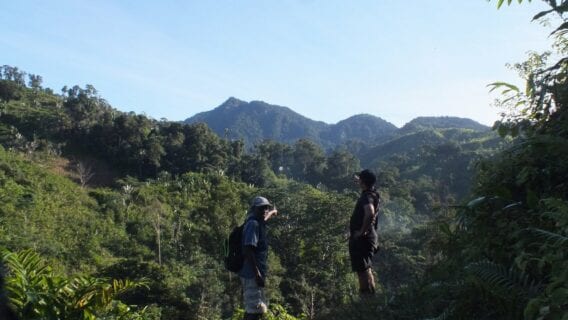

Recognising and respecting indigenous lands and tenure is a fundamental first step and can enable indigenous-led conservation efforts. Recognition of Indigenous land tenure also aligns with international guidance contained in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). In Papua New Guinea, the country’s Indigenous peoples own over 95% of land. To implement a conservation project for the Endangered Huon Tree Kangaroo, an IUCN Save Our Species project worked with local communities on land planning consultations, introducing mapping and demarcation of the project areas to understand land ownership.

Creating collaborative management arrangements.

Many protected areas now engage in collaborative planning and management processes that respect free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC), incorporate local voices and visions, and include Indigenous leaders and elders in decision-making bodies. In Canada, for example, decisions made in Torngat Mountains and Gwaii Hanaas National Park Reserves are guided by co-management bodies that include strong Indigenous representation in co-management arrangements. Also, outside protected areas, local communities are engaging in a diversity of conservation projects and initiatives, ranging from the creation of sustainable forest use zones to setting up ecotourism ventures.

Recognising Indigenous and Community Conserved Areas.

Globally, Indigenous and Community Conserved Areas (ICCAs) are being created and managed by Indigenous communities themselves. In some countries, ICCAs have legal recognition and government support. In Mexico, for example, some communities register their lands and territories as voluntary conserved areas. This allows communities to access government resources and technical support, as well as protect their lands from extractive industries and other development endeavours.

Incorporating indigenous knowledge and practices.

Indigenous worldviews, customary management practices, and traditional knowledge can be incorporated into management decisions, making them more effective and culturally appropriate. For example, in Indonesia, an IUCN Save Our Species project worked closely with religious groups and local communities to protect and raise awareness of the critically endangered Giri Putri Cave Crab. The crab, endemic to the Holy Caves of Goa, was being threatened by the increasing use of the caves by pilgrims and worshippers, as well as tourism.

Affirming and integrating harvesting rights.

Since sustainable use of resources has often been part of indigenous stewardship efforts, subsistence harvesting practices should be supported as part of wider conservation strategies. In Madagascar, there are traditional local laws called dina, which restrict destructive fishing practices and enforce temporary closures of fishing grounds and mangrove reserves to ensure species are able to reproduce and thrive.

Providing capacity building and financial support.

Supporting local leadership capacity requires financial support, training and educational programs, and employment opportunities, which must be made directly available to Indigenous peoples and their organisations. For example, in one forest in Madagascar, an IUCN Save Our Species project is empowering the local community to conserve Lemurs by introducing educational programmes, creating additional jobs and developing alternative income sources to alleviate human pressure on the forest.

Documenting and managing social impacts.

Understanding how conservation initiatives have or will impact Indigenous communities can help managers or management bodies understand how to mitigate those impacts. Across all IUCN Save Our Species and Tiger Programme projects, the IUCN’s Environmental and Social Management System is used in order to ensure local communities are not disadvantaged by conservation projects. These are established and monitored rigorously as projects are implemented.

It is evident that effective conservation requires genuine collaboration with and substantive support for Indigenous peoples. Respecting, recognising and actively backing Indigenous leadership in terrestrial and marine conservation improves legitimacy and chances of long-term success. The survival of our species depends on right relations with nature as well as Indigenous peoples.

The Commission on Environmental, Economic and Social Policy (CEESP) contributes to the IUCN’s Mission by generating and disseminating knowledge, mobilising influence, and promoting actions to harmonise the conservation of nature with the critical social, cultural, environmental, and economic justice concerns of human societies. One important area of focus is Indigenous people and conservation.